Designing for Academic Integrity

Although it is impossible to prevent all students from engaging in academic misconduct (in person and online), there are plenty of ways to reduce the chances for it.

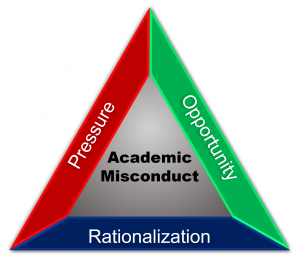

To provide a framework for understanding the elements that can lead to academic misconduct, we share the Cheating (or Fraud) Triangle model proposed by Choo and Tan (2008). The model, discussed in brief here, suggests that the three main elements that impact academic misconduct are:

-

- Opportunity

- Rationalization

- Pressure

Further, the authors argue that by targeting these elements through course design and assessment practices, the propensity to cheat among students can be reduced.

Image retrieved on August 18, 2020 from https://blogs.ubc.ca/assessmentguidebook/academic-integrity/the-fraud-model/

Since academic integrity encompasses a set of values that are supported by university policy, we provide suggestions below that can help to address these drivers of academic misconduct.

Practices to consider when designing your course

If you have not yet designed your syllabus or decided on assignment weights, here are some academic dishonesty prevention practices that you could consider as you develop specific assessments. The Academic Integrity Course Design checklist will help you cover the important components of designing courses that promote Academic Integrity and mitigate dishonesty practices.

Reduce the pressure to cheat by considering how the course assessments fit into the appropriate expectations for a 3 credit course.

Mitigates: Stress and Pressure, Rationalization

Expertise-appropriate assignments: When trying to determine the appropriate number and frequency of readings and assignments, consider the fact that as a recognized expert in your field, your estimation of the length of time needed to read a text or complete an assignment may not match up with the expertise level of a student. (TIP: try to do the assignment yourself and multiply the time it took you by 3). You might also want to determine whether the assignment assumes knowledge of skills that are not being taught in the course, like working effectively with a group, video editing, etc.

You may find that you need to adjust expectations to prevent overload using UBCO’s Student Course Time Estimator. This estimator makes transparent the amount of time it might take a student to complete all course readings and assignments.

Implementing a quiz before introducing new material can serve as a self-assessment of students’ knowledge and can also promote curiosity (graded or not graded). This can help students focus on their learning by bringing attention to misconceptions, relevant knowledge already acquired, and a set of questions to guide their learning ahead. Consider using Qualtrics for surveys, Canvas for quizzes, Zoom or iClicker Cloud for polls.

Mitigates: Rationalization

More information on formative assessments.

By making the overall grade for assignments, labs, projects, etc. worth more than the total marks of the midterm/exam, students will be supported to learn throughout the course instead of focusing on one or two opportunities to succeed (be sure to align with UBC’s policies on examinations as well as your Faculty’s policies).

Mitigates: Stress and Pressure

More information on summative assessments.

By reducing pressure on heavily weighted exams that happen at the same time in students’ multiple courses, implementing several, low-stakes assessments can reduce cheating. There is less motivation to cheat when only a few marks are at stake. Such strategies can include dividing midterms into weekly quizzes and the results of these quizzes can further inform your teaching and learning practices.

This frequent and early feedback can also provide students with a better idea of how they are doing in the course and offer more opportunities to improve. Keep in mind: if all courses implement this strategy, then pressure on the part of the students would actually increase. Thus, use this strategy with caution and, if possible, in consultation with your colleagues.

Mitigates: Stress and Pressure, Temptations & opportunities

Adding flexibility to the weight of your multiple assessments allows students to focus on learning instead of their grade and reduces the pressure of having so much of a course’s weight rest on one assignment. When this flexibility is built into the course, it will be most effective when accompanied with a clear policy. For example: “I will only count the best 5 of 6 quizzes during the term”.

Mitigates: Stress and Pressure

Practices to consider when developing specific assessments

One impactful approach is to re-imagine the ways we assess student learning. As a general rule, authentic assessment methods accompanied by clear rules have been found to be associated with reduced academic misconduct (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006). Once you have designed your syllabus and decided on assessment weights, here are some practices to help reduce academic misconduct as you create specific elements of an assessment. The suggested practices tackle each of the three components of the Cheating Triangle Model: opportunity, rationalization, and pressure.

As you reflect on the suggested assessment strategies, consider the following:

-

- your resources to mark and provide timely feedback to students

- your discipline

- the number of students in your course

- the balance of assessment strategies in your course throughout the term

- your overall familiarity with new technologies (reach out to the CTL Helpdesk for help with UBC available technologies)

- your department/Faculty policies and practices

Clearly communicating your expectations of any assessment strategy is a requirement (learn how to communicate with students through Canvas). The Academic Integrity Course Design checklist is intended to guide you towards thoughtful assessment design and communication of assessment expectations to students.

Consider alternatives for “easy to cheat” questions. For example, instead of the classic true/false or multiple choice questions, try matching exercises or automatically generated individualized questions.

Mitigates: Stress and Pressure

Opportunities for self-assessment (surveys, quizzes, polls, etc.) give students a sense of responsibility for their own learning, and a sense of familiarity and comfort with the material.

Mitigates: Rationalization, Temptations & opportunities

An excellent way to assess students’ learning is to provide them with opportunities to apply their knowledge. This can be done through case studies, for example. The closer the scenarios/cases are to reality, the more authentic your assessment. It will be harder to cheat with case studies since they target higher levels of learning (application, analysis, critical thinking).

Mitigates: Stress and Pressure, Rationalization

An effective way to do this is through problem-solving questions which require students to consider multiple aspects of the course and possibly other courses as well. Here are three easy steps for implementing problem-solving questions:

- First, outline a problem (the closer they are to a real-world situation, the better)

- Then, remove the ending of the problem (i.e., the solution)

- Now, ask your students to think of different solutions. Ask them to explain why they chose a specific solution and how they could have chosen alternate paths to arrive at the same ending.

Mitigates: Stress and Pressure, Rationalization, Temptations & opportunities

Take the time to clearly explain the reason(s) behind your course’s assessment methods. Doing this will significantly increase the students’ sense of agency and responsibility for their own learning. One approach is to add a short explanation for each assessment method: how it aligns with the targeted learning outcomes and how it may impact the students’ current and future career. (See suggestions for syllabus language)

Mitigates: Rationalization, Temptations & opportunities

Within your assessment, consider adding an opportunity to comment where students can let you know about ambiguous and/or unclear questions. You may also create a formal mechanism for students to challenge a question from the quiz. This provides you with the opportunity to respond in a timely manner and make changes as needed. Giving students the chance to communicate with you in this manner also strengthens your relationship with them.

Mitigates: Stress and Pressure, Rationalization

Apply all policies fairly and with compassion (Academic Honesty and Standards; Academic Misconduct). Your students need to know that integrity is expected and valued. Academic misconduct isn’t always dishonesty and students who cheat do not always have bad intentions. Sometimes these actions stem from a lack of confidence, poor academic skills, a genuine misunderstanding, or just a bad decision due to stress. The goal is to help students learn and grow from their mistakes (See suggestions for syllabus language).

Decisions surrounding academic integrity need to be balanced with considerations of equity as well, especially considering access to technology and recognizing the many barriers that students face. Instructors should strive for consistency where possible, but within an equity framework.

AIM Program Resources for Academic Integrity

The AIM Program has Canvas courses on academic integrity available for faculty to assign to students in their classes for credit. Once a student completes an AIM course, they are awarded a Certificate of Completion.

Additional Resources

References

Choo, F. and Tan, K. (2008). The effect of fraud triangle factors on students’ cheating behaviors. Advances in Accounting Education: Teaching and Curriculum Innovations, 9, 205–220.

Christensen Hughes, J.M. & McCabe, D. L., (2006a). Understanding academic misconduct. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 36(1), 49-63 . Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268254674_Understanding_Academic_Misconduct

Lederman, D. (2020). Best way to stop cheating in online courses? “Teach better.” Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from: https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2020/07/22/technology-best-way-stop-online-cheating-no-experts-say-better

Ostafichuk, P. (2020). Misconduct framework. Remote Assessment Guidebook [UBC blog] Retrieved from: https://blogs.ubc.ca/assessmentguidebook/academic-integrity/the-fraud-model/

Malamed, C. (2010). Tips for writing matching format test items. The Elearning Coach. Retrieved from: http://theelearningcoach.com/elearning_design/writing-matching-test-items/

Shift ELearning (2018). 6 ways to assess your students. Shift Disruptive Elearning. Retrieved from: https://www.shiftelearning.com/blog/ways-to-assess-your-students-in-elearning